Lincolnshire’s Finest Chocolate

When Cleethorpes chocolate aficionado Duffy Sheardown discovered that only one UK manufacturer still made chocolate using proper cocoa beans, he set out with a simple mission: to make ‘the best chocolate bar in the world.’ Within just 12 months he achieved his ambition and so much more. Now, just in time for Easter, Duffy spills the (cocoa) beans, revealing everything you’ve ever wanted to know about chocolate

Duffy really only has one rule. Melt, don’t munch. I’ll add another rule to his; eat less but better. For weeks, perhaps even months now, the supermarket shelves have already been heaving with Easter confectionery: chocolate bars, eggs, truffles and novelty figures like Easter bunnies. But whilst we’re not short of choice, there’s really not much to separate them in terms of quality.

It’s reckoned that each of us consumes about 8kg of chocolate a year, about 600,000 tonnes as a country, and some of our most well-recognised brands are a venerable presence on the shelves.

Easter eggs were first sold by Fry’s in 1873, then Cadbury from 1875. Some well-known brands date back to the 1920s in the case of Cream Eggs (originally a Fry’s product, only branded Cadbury from 1971), Cadbury’s Flake, the Fruit & Nut bar and Crunchie, or from the 1930s in the case of the Mars Bar, Milky Way, Kit Kat and Maltesers.

The trouble is, whether you opt for a mass-market brand or buy chocolates from a premium retailer, it’s all basically a mish-mash of beans from different places and of varying quality, often with much of the expensive cocoa butter taken out, replaced by milk powder, sugar and worst of all, vegetable or palm oils.

Happily there is an exception. In 2008 Cleethorpes’ Duffy Sheardown was surprised to hear on a Radio Four food programme that there was only one company in England (Cadbury) still making chocolate using cocoa beans.

Otherwise the chocolate that we see on the supermarket shelves is imported from overseas ready to be melted and utilised in the production of familiar chocolate products.

Even independent artisan chocolatiers (and chefs) use wholesale products – the best quality being chocolate callets from Callebaut or Valrhona – to make truffles or novelty shaped chocolate figures.

“I went on holiday to Guatemala a year later and purchased a couple of bags of cocoa beans, then spent 18 months at home learning how to roast chocolate,” he says. “18 months later I took the plunge and became the first small artisan bean-to-bar chocolate company in the UK.”

Arguably, large-scale production of anything necessitates compromise. Making bread as an artisan baker means giving your dough time to prove and rest, but industrial bakeries employ the Chorleywood bread process, invented in 1961, to go from flour to packaged loaf in less than three hours.

Making tea or wine in supermarket-satisfying volume, meanwhile, means sourcing leaves or grapes from different estates and blending them to create a mass-market product with consistent characteristics – or producing in smaller quantities products like single-estate tea or wines with appellation d’origine contrôlée or denominazione di origine controllata garantita designations.

Chocolate is a product similarly afflicted. Those processing chocolate on an industrial scale necessarily source beans from different chocolate cooperatives, blending them together with other ingredients like sugar and milk solids to mitigate the inconsistency.

By contrast, Duffy often purchases his chocolate from a single plantation, and in much smaller quantities, ensuring he can produce single estate chocolate using cocoa beans from one particular supplier.

The more artisanal nature of this business model also allows for the formation of good relationships with the farmer, who can be paid three or four times more because they’re not in such a convoluted supply chain (Fairtrade-affiliated cocoa growers, for example, have to be part of a cooperative), and whose welfare Duffy can vouch for.

“Back in 2009 you could purchase either a handful or beans, or 20 tonnes… thankfully there’s a happy medium now,” says Duffy.

“We tend to buy about 500kg of cocoa beans at a time, in 60kg sacks, which is enough to make craft chocolate in a quantity that’s viable, but ensures we can still have a direct relationship with the farmer.”

“Producing craft chocolate requires the best quality beans – without good ingredients you’ll never achieve a good product. Cocoa grows best in wet, hot climates, so it’s a variable product, which is why it helps to produce artisanal quantities of chocolate rather than industrial quantities.”

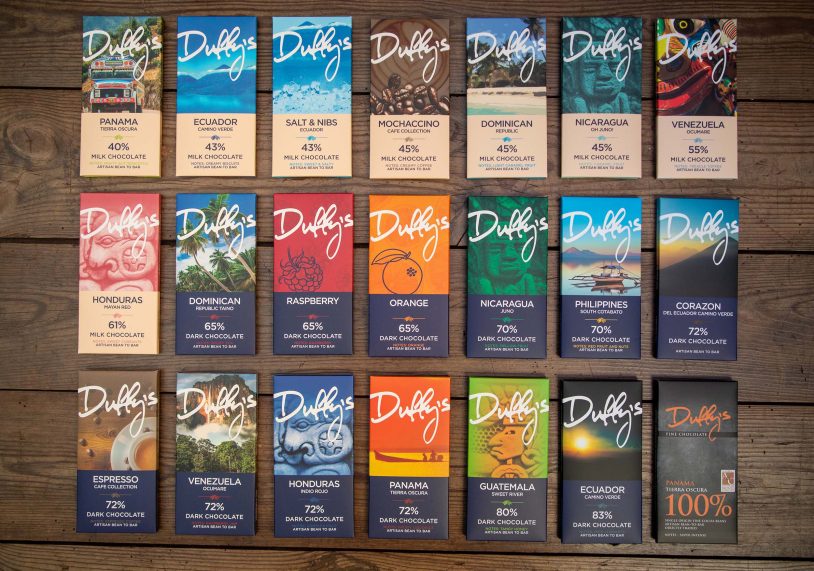

Beans from different areas have different characteristics. Duffy purchases beans from around seven countries and can identify subtle nuances in each region from the floral taste of Ecuadorian beans, notes of pineapple or tea in beans from the Dominican Republic, dark, figgy flavours in Nicaraguan cocoa or the nutty, treacle or toffee flavours in Venezuelan beans.

“The aim is to express the flavours that are already in the beans, allowing them to come to the fore,” says Duffy. “Firstly we spread the beans over a perforated tray and roast them for about 25 minutes at 130°c, although there’s always a degree of nuance and judgement from variety to variety and batch to batch.”

“They’re cooled overnight and then need winnowing, a term that’s more associated in the West with cereals farming, blowing air through grain to separate the chaff.”

“The labour-intensive way to achieve that is to spread the chocolate beans on a tea tray and then throw them in the air, which is what I did in the beginning, but thankfully I’ve moved on a little since then.”

Duffy has a bean breaker and a winnower: the machines cracks the bean into a flow of air, ready for the husk to be blown away, leaving just the bean itself, ready for refining.

The bean without its shell is now more correctly referred to as a nib and so the nibs are put into a stone grinder, 18kg at a time, and ground overnight, turning them from a soil-like texture into a paste, the consistency of which is akin to peanut butter.

Sugar is added and up to 10% cocoa butter, then the beans are refined for a further three days, with the addition of warmth from a heat lamp. The chocolate is then cooled overnight before being left for three months in airtight containers for its flavour to develop at which point the fat in the cocoa butter will form a white-ish bloom over the surface. Perfectly safe and natural, it’s the result of chocolate absorbing moisture, which then crystallises on the surface.

Finally a tempering machine heats the chocolate to 45°c, cooling it to 29.5°c and keeping the now liquid cocoa conditioned, dispensing it at a precise 60g at a time into Duffy’s bar-shaped moulds which are then put into the fridge to set before being wrapped by hand.

Duffy reckons he makes over 30,000 bars of chocolate a year and there are no fewer than 23 varieties with varying cocoa percentages and different geographical origins of the beans.

We were treated to a comprehensive chocolate tasting experience which was a fascinating way to have my preconceptions of chocolate tested. I admitted to favouring milk chocolate and usually consider darker chocolate too bitter. In fact, having sampled Duffy’s 70% and 72% bars, I found they’re incredibly smooth and even Duffy’s 100% Panamanian chocolate was much smoother than mass-market ‘dark’ chocolate. I could happily enjoy a bar of it despite its huge cocoa content.

As for the different origins of the cocoa beans it is possible to taste some really profound differences. Duffy does produce espresso, raspberry and orange-flavoured chocolate bars too, but really we’ll advocate the unflavoured bars which really do let the nuances of each region come to the fore. I’ll contradict myself here though and state that my absolute favourite among Duffy’s portfolio of fine chocolate was his fabulous Ecuadorian Salt & Nibs milk chocolate with its smoked sea salt.

The latter is absolutely the most delicious chocolate I’ve ever experienced, but if you want to sample just one bar, make it Duffy’s Honduras 72% Indio Rojo which was officially named as ‘the best chocolate bar in the world’ by a panel at London’s Academy of Chocolate.

Another note on tasting; mass market chocolate often has (expensive) cocoa butter taken out, sometimes sold to the cosmetics industry, then replaced with vegetable or palm oils along with sugar and milk solids. The result is chocolate which can be chomped and melts more readily. When you’re enjoying Duffy’s chocolate though, just let it melt, slowly, on your tongue, perhaps closing your eyes and taking in the flavours… I guess that advocates a sort of mindful tasting, slowing down the experience and making it a luxurious treat to be savoured.

Naturally there’s a premium for Duffy’s chocolate over mass-market chocolate, but it’s such an intense and more refined flavour that, in fact, you need less of it… eat less, but better, remember?

For those who want to broaden their chocolate palate, Duffy’s individual bars are available from about £5.65 but he also offers gift sets with two or three bars.

His taster Selections (five bars with different characteristics) are priced from £29 for dark, flavoured or taster selections, to £32 for a selection of five bars which have so far won no fewer than 49 awards).

There’s also a subscription option too, with three or six month subscriptions… a gift that keeps on giving!

For the full experience, Duffy also offers chocolate classes and parties. For up to 16 children that means making and decorating chocolate lollies, whilst adults enjoy tasting, dips and make truffles to take home, plus they gain a complete cocoa education.

Sessions last up to 90 minutes and can be pre-booked for an experience any self-respecting chocolate-lover will really enjoy.

However you enjoy Duffy’s chocolate though, you’ll never look at the stuff the same way… his artisanal bars are the ultimate expression of cocoa indulgence!

To purchase Duffy’s bars or enquire about chocolate experiences, call 01472 211107 or see www.duffyschocolate.co.uk