Reap What You Sow: Tim’s Harvest…

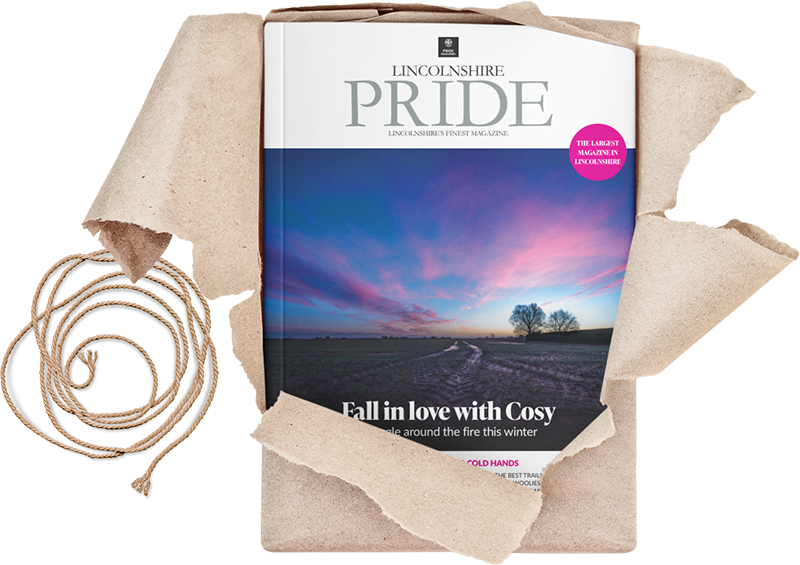

At the time of writing, Lincolnshire’s skies are blue, temperatures are high and the county’s fields are golden brown. This month we’re sitting cabside with World Champion farmer Tim Lamyman who enjoys gathering in the harvest on his farm in the undulating Wolds…

In A Year Of Uncertainty, a bit of familiarity can prove a real comfort. The sight of the combines, rolling around the fields, reminds us that nature is a constant, even in volatile times. A couple of times when discussing the consequences of lockdown, I’ve heard businesses remark that all of a sudden their plans, budgets and financial forecasts have been turned completely on their heads. They’ve spoken about how disconcerting such uncertainty is.

And yet that’s a condition which farmers have had many years to get used to… if not tolerate. Everything can be going well until those vital weeks leading up to harvest and a whole year’s work can be upset. Uncertainty and being at the mercy of nature is something that goes with the territory for farmers, and you have to wonder how they cope.

“You get on with it,” says Tim Lamyman philosophically. “You accept the ups and downs and try to foster a sense of resilience, much like you do in any other aspect of life.” Easier said than done with such important consequences, but if anyone should know, it’s Tim. The farmer is the third generation of his family to tend the fields of arable crops on his land, exactly equidistant between Louth, Horncastle and Alford… he’s in the centre if you were to draw a triangle between the towns.

Tim farms over 1,500 acres plus a further 400 acres under contract and his entirely arable operation comprises wheat, barley, peas and beans as well as hay and haylage. But Tim is no ordinary farmer. Whilst wheat yields an average six and a half or seven tonnes per hectare, Tim’s whopping world record winter wheat yields topped 16.5t/ha in 2015. He has also achieved pea yields of 7.5t/ha in 2019 breaking that world record for a second time and he has achieved barley yields of up to 13 t/ha.

“It’s a matter of pride I suppose, but the whole farming industry has to stay sharp and continue to innovate,” says Tim. “We need to feed an ever growing population and improving farming practices is a hard fight, but a good one.”

“We practise a high input and high output model which in simple terms means putting lots of effort in and using different varieties to ensure resilience. I’m planting KWS Colosseum and Parking wheat, and a few others.”

“The farm also uses a range of different nutrition, not just fertilisers but other inputs to de-stress the roots and lower the risk of fungus as much as possible. It’s not a cheap way to farm, but the results are there.”

Tim’s cereals will be sold for milling, for animal feed and for seed production. Naturally he’s been called upon to give talks on increasing yields across the industry and is proud not just of his own efforts but the whole of the farming sector in Lincolnshire.

It’s also fair to say that Tim’s job isn’t made any easier by virtue of the fact that his land isn’t flat, as is the perception of Lincolnshire from outsiders. Yellowbellies are familiar with the gentle undulations of the Wolds, but none more so than the poor farmer who has to try to achieve consistent results from the hilly region.

By the time this appears in print, Tim will be well into sowing oilseed rape and wheat, doubtless with cooler weather and murkier skies. But at the time of writing, in mid-August, the skies are a dazzling blue with cotton wool clouds and temperatures in their mid to late 20s. And where better to take in the view of the Wolds on such a splendid day than through the windscreen of Tim’s Claas Lexion 750.

Tim’s combine is a whopper, boasting some 550hp of grunt, weighing in at a hefty 16 tonnes and capable of swallowing up 11,800 litres of grain before offloading into an amenable tractor and trailer.

For a monster machine though, it’s a pretty civilised experience. Beginning at around 10am, by which time any morning dew will have evaporated off the crop, Tim enjoys the civility of climate control set to a fresh 19°c and switches between the equally patriotic Lincs FM and BBC Lincolnshire whilst trundling methodically round each field at a leisurely 25mph.

Some combines can sport a header of up to 50 feet, but the one of Tim’s Claas is a little more modest at 25ft because of the tricky turns and undulating grounds it has to traverse on its combination of tracks and wheels. The term combine harvester refers to a consolidation of the roles of cutting, and threshing to separate the crop from its unwanted stalks and chaff which are then chopped and spread.

Despite its macabre appearance the adjustable header’s job is simply to comb the crop and feed it uniformly into the combine’s jaws in preparation for the reciprocating row of teeth to cut the crop at its base.

The crop is then sent by conveyor towards the threshing drum which spins at anywhere between 160 and 900rpm depending on the crop being harvested. Grain falls through sieves to the collecting tank and is taken by auger towards the grain tank, whilst the rotors take the rest to the rear of the machines where rotating choppers cut and spread the straw ready for baling.

Modern combines have become increasingly clever and can drive themselves using GPS but beyond his laser pilot – a device which assists in maintaining straight lines – Tim prefers to pilot the machine manually. His working day continues until dusk, or mist or the desire to go in for a bit of supper, if time allows. From his father Peter’s day and certainly from grandfather Leonard’s day, the industry has changed significantly, but as Tim’s yields prove, technology is an ally at most, rather than a substitute for the good judgement and experience of a farmer.

“My son Robert is 20 and has just finished his agriculture Foundation degree at Bishop Burton and is already helping on the farm. My daughter Emma is a bit younger and helps my wife Sarah with the luxury holiday cottage we’ve created on the farm, Woody’s Top.” Emma starts work at a local accountancy firm in September.

“It’ll be interesting to see what the future of the industry is,” he says. “But even though we can’t predict how farming will change, and especially the farming of cereals, we can say with reasonable certainty that it will remain an important part of the sector, one that I hope will always be as much of a challenge and a pleasure as it is right now!”