Remembering Ingram

Boston’s most famous son Herbert Ingram founded pictorial journalism and brought water, gas and railway connectivity to Boston. The MP was much beloved by his townfolk who mourned his premature death, but though Ingram is gone, his legacy remains…

It’s 13th October 1860. The autumn rain is siling down on the platform at Boston train station, on the Boston, Sleaford & Midland Counties railway line which opened just two years before. Despite the weather, 10,000 people have turned out to witness the return of one of Boston’s most famous sons, Herbert Ingram, and to join their townsfolk in mourning his loss. It would be one of the largest funerals the town has ever seen.

The population was heartbroken by the loss of its MP, who had done so much to provide Boston not just with representation in parliament as its Liberal Party politician from 1856 to 1860, but as someone who was pivotal in bringing piped water to the town and helping to develop its gasworks prior to the proliferation of electricity.

But those were just Ingram’s local legacies. He also pioneered the popularisation of pictorial (i.e.: image-led) journalism, a concept that pre-empted by a number of years tabloid journalism, newsreels and pictorial broadcasts – even picture and video content on social media.

It’s no understatement to suggest that Ingram pre-empted the media in the form we know it today, and whilst his Illustrated London News ceased publication in 2003, the company he founded is still in existence today. But Ingram’s story began far from the austere Gothic Revivalist enclave of Westminster and its palaces – which, at that time, were being rebuilt following a fire in 1836 – and to understand Ingram, we need to look to Boston, not London.

Herbert was born on the town’s Paddock Grove, just off Boston’s West Street, on 27th May 1811, and was the son of butcher Herbert senior, and his wife Jane Ingram, née Wedd. The older Herbert died when his son was young, and the young Ingram was raised in poverty along with his sister, attending the Laughton’s Charity School, which operated in the south-west chapel of St Botolph’s, and the town’s National School on Wormgate and in Pump Square.

Leaving school at the age of 14, Ingram was apprenticed to a printer in the town, Joseph Clark. Well-read and a canny businessman, Clark praised Herbert’s patience, industriousness and determination. In return Ingram worked hard and took a conscientious interest not just in Clark’s printing business but in his side-line, as a chemist peddling by ‘prescription’ medicines, sold as Victorian miracle panaceas!

Upon completion of his apprenticeship, Ingram moved to London and by the age of 21, was working as a machine printer in the city before returning to Nottingham at 23 years of age to found a business as a printer and newsagent – Ingram, Cooke & Co – in partnership with his well-educated friend and later, brother-in-law, Nathaniel Cooke. Nathaniel, incidentally, was also the author of a number of chess columns for newspapers and was the designer of a set of chess pieces which became the de facto standard set of playing pieces we know today.

The company predominantly published travel guides and history books, but as a retailer Ingram noted with interested that when newspapers of the day featured illustrations, their sales increased dramatically.

That can partly be explained by the fact that Victorian society was less literate than today, but it resonated particularly with Ingram who was a poor writer. Cooke, by contrast, was highly literate and so the entrepreneurial spirit of Ingram and the literacy and intellect of Cooke would prove ideal for their future business success… but first, they needed capital.

Fortunately, Ingram always devoted a corner of his shop to health pills, perhaps to acknowledge his gratitude to his old boss Joseph Clark. Ingram & Cooke happened across a supposed descendent of folklore figure Old Tom Parr – who died some 200 years earlier but who was reported to have lived to 152 years of age.

This longevity was credited to the miraculous effects of a vegetable pill created by Boston quack Dr Snaith. Purchasing the recipe, Ingram began to sell Parr’s Life Pills and would use the money from dubious pharmacology to fund their next venture.

Less literate but a great businessman and rather ruthless, Ingram also had a principled belief that topical news should not be the preserve of the wealthy and literate. With that in mind he returned to London and established Ingram & Cooke at 9 Crane Court in Fleet Street where they would publish the first edition of The Illustrated London News on 14th May 1842. The first edition had 16 pages and 32 illustrations.

With its first editor Frederick William Naylor Bayley (a poet known informally as Omnibus or Alphabet) at the helm, it targeted a broadly middle-class readership and enjoyed immediate success, printing 26,000 copies.

The ILN was a weekly publication from 1842-1972, on sale each Saturday, before being published monthly from 1971-1989; quarterly from 1989-1994 and then finally biannually from 1994-2003. Within just a few months of publishing its first edition, the ILN was selling 65,000 copies per edition, and charging high prices for advertising, yielding profits of £12,000 a year (about £950,000 in today’s money).

For context, at the time of Ingram’s death the ILN was selling 300,000 copies a week whereas The Times was selling just 70,000 copies, albeit daily, as a newspaper.

To somewhat state the obvious, central to the ILN’s philosophy was the idea that news should be illustrated, and though photography was invented about 20 years before, and was just establishing itself for the purposes or portraiture, reprographic technology was yet to catch up. The ability to replicate the clarity of a photograph using established printing techniques was somewhat lacking. To overcome to issue of illustrations, Ingram relied heavily on established wood-engraving artists, persuading them that working for a weekly news publication was not beneath their talents.

Among them was a young John Gilbert, headhunted from Punch magazine, who contributed to the debut edition’s engravings of Queen Victoria’s masked ball, and who would later illustrate Shakespeare’s collections, then contribute 60 portraits to the British National Collections and would be knighted a few decades later. Other artists included Birket Foster who created chocolate box illustrations for Cadbury, and Harrison Weir, who is credited with organising the first cat show in England at the new Crystal Palace and founding the National Cat Club.

Illustrations were created, in reverse, on different wood blocks measuring two or three inches each, allowing multiple artists to work on a single overall image – for instance, for a larger illustration one artist might work on the sky, another on the subject and another still on the background elements.

A double page spread image might have comprised no fewer than 40 blocks joined together to create the final illustration, an endeavour made even trickier following the introduction of colour to the publication with a special Christmas supplement in 1855.

The first edition included coverage of the first Anglo-Afghan war, the Versailles rail accident which cost up to 200 lives, and the presidential election which would see John Tyler become the tenth President of the United States. To promote the new publication, Ingram employed 200 people to walk through the streets of London carrying placards announcing its launch.

The debut was an instant hit and happily its release coincided with the first masked ball at Buckingham Palace, with Queen Victoria appearing in eight of Scott’s illustrations as Philippa, Queen of Edward III ‘in a velvet skirt with a surcoat of brocade, blue and gold, lined with miniver.’ The Queen’s consort Prince Albert appeared as King Edward, wearing a scarlet cloak lined in ermine.

Still today every publishing operation should expect the unexpected, usually on deadline, immediately before publication. And sure enough just before the ILN went to press with its debut edition news reached Fleet Street of a great fire breaking out in Hamburg.

With no images able to be transmitted in that era, Bayley sent a member of his editorial team to the British Museum to source an image of the city. ‘Journalistic license’ was then employed to add in flames, smoke and shocked onlookers, proving that even 145 years prior to the invention of Adobe Photoshop, images in the press can’t always be trusted!

The first edition of the publication enjoyed a great response, but the ILN soon proved that it wasn’t averse to publishing hard-hitting stories – nor to criticism of the establishment. The second edition proved a stark contrast to the joviality of the debut newspaper’s images of the Royal Masked Ball, carrying instead a revealing story about the work of children in mines.

‘At this moment of festivity and enjoyment, when the youthful Sovereign of a mighty empire is happy in the possession of her people’s love and her courtiers’ adulation, we are reluctant to throw the gloom of reality over the bright and laughing influences of the hour, but […] there is irrational suffering in the mine […] children of the Sovereign […] are tended with all the affection of parental love [whilst] her subjects are, for want of legislative protection, deprived [and conditions are] so revolting to humanity […] that it is hardly possible to approach the subject with patience. We, as a people, have been weighed in the scale and are found wanting.’ Hyperbole I’d be proud of.

The ILN was, in addition, keen to include war reporting as part of its content, sparing readers none of the realities of conflict: the 1848 révolution de février in Paris; the Crimean War of 1853; the US Civil War and latterly the first Boer War in 1880.

Correspondent and illustrator Constantin Guys covered Paris and the Crimea – the latter as one of six members of staff sent to the front line. He and his peers would make rough sketches of battle before returning to the safety of their camp to refine his work.

By the time the Crimean War broke out, one of the earliest war photographers, Roger Fenton, was capturing the explicit horrors of warfare using long-exposure photography which would then provide the source material for the ILN to create its woodblock engravings. Another success of the ILN was its periodic musical supplements including original songs written by members of staff like poet and musician Charles Mackay who penned patriotic songs like ‘England All Over!’ and ‘There’s a land, a dear land!’ or ‘Cheer, boys, cheer!’ and disseminated them exclusively though the publication.

Sales of the ILN swelled to 200,000 copies during its coverage of the Crimean War, and abolition of the penny duty on newspapers in June 1855 – for which, for obvious reasons, Ingram was a strong advocate – created a booming market in which 168 newspapers were launched over the following year.

Ingram was a canny businessman with deep pockets and wasn’t about to let upstart competition encroach on his territory. The ILN swallowed up Lloyd’s Illustrated Paper, The Pictorial Times, The Lady’s Newspaper and The Illustrated Times.

Ingram became the Liberal Candidate for Boston in 1856, telling the people of Boston they needed ‘a representative who is at once the product and the embodiment of the progressive spirit of the age,’ a stirring message, it ensured Ingram won by a landslide – 521 votes to 296 – despite criticism in rival papers that his newspapers’ propaganda played a part in ensuring his victory.

Herbert nonetheless made good on his election promises and campaigned for social reform in the House of Commons right up until his death.

Ingram was undoubtedly willing to use those whose talent he employed to the fullest of their skills, even if he did rarely give them the credit they deserve for their part in his success. In his most successful later years, he drank heavily and was intolerably inflexible and grumpy even to his closest and most talented colleagues. Having married Ann, a wealthy farmer’s daughter from Eye near Peterborough, the couple had ten children, of which nine survived.

Herbert Ingram regularly stayed in Boston and in 1851, purchased the patronage of the vicarage of Boston for £1,050 (about £135,000), and invested heavily in its restoration with Nottingham Architect and Gilbert Scott, culminating in new stained-glass windows and with the new baptismal font carved by Augustus Welby Pugin.

Ingram also ensured that children could be educated in the church, recognising that educating young Bostonians could create more entrepreneurs like himself in the future.

A long-standing frustration with his townsfolk was the lack of piped water, and still water was being sold by the bucket from water carts in the Market Place or obtained manually from the public pump in Pump Square, served by two underground cellars that functioned as reservoirs.

Determined to address this deficiency, Ingram created the new Boston Waterworks which were based about 12 miles north of the town in Miningsby, elevated 170ft higher than Boston’s streets, enabling water from the reservoir he created to flow naturally through 12” diameter pipes.

The businessman’s determination that the town should be connected to the booming British railway infrastructure was recognised in 1852 with the Boston, Sleaford and Grantham Branch Line of the Boston, Sleaford & Midland Counties railway created to link to the Great Northern Railway line.

It’s believed that Ingram was also a key investor in Boston Gas Light and Coke Company, which was formed earlier, in 1824 and located near to the town’s Grand Sluice, remaining until 1949 when it was nationalised. The public would have no doubt recognised Ingram as a key reason that Boston gained the modern utilities and infrastructure of the age.

Elected again in 1857 and 1859, sadly his tenure as MP and a major benefactor to the town was to be cut short. Whilst on a trip to the New World with son (also called Herbert) to obtain illustrations for the ILN, Ingram took an ill-fated trip on the paddle steamer The Lady Elgin on 8th September 1860.

In the early hours of the morning the ship collided with the schooner Augusta off the coast of Winnetka, tearing off the paddle box and cutting through the cabin. Despite best efforts by Captain Jack Wilson, all 400 passengers on board all died, the boat sinking within half an hour of the collision.

It’s believed that Ingram was struck by one of the stray timbers. His body washed up on the shore of the lake and was recovered, but the younger Herbert’s body was never recovered and today the obelisk erected to honour Herbert Ingram features a cast of the younger man.

Control of the ILN passed to Ingram’s widow Ann and latterly to his son William in 1874 and Sir Bruce Ingram from 1905. The latter would run the ILN for 63 years before selling the firm to Roy Thomson and then to Sea Containers, becoming part of a luxury travel and lifestyle magazine portfolio.

The ILN was relaunched in 2003 under its last editor, Mark Palmer, before a management buyout in 2007, following which the company’s name endured whilst the title itself folded. Today, ILN is based in Spitalfields and provides marketing services to luxury brands publishing, for example, the contract magazine title sent out free to owners of Aston Martin motor cars. The company also owns and manages the rights to the entire ILN archive.

Back at the rainy railway station, though, Herbert Ingram’s body arrived in the town, having departed on Friday, 14th September 1860, from Toronto, travelling to Liverpool and the Great Western Railway, in the care of his uncle Nathanial Webb.

The train arrived in Boston at 1.50pm the following Thursday and was met by the Rev J Yarbugh, who would conduct Ingram’s funeral before his burial in Boston’s cemetery, created just five years previously in 1855.

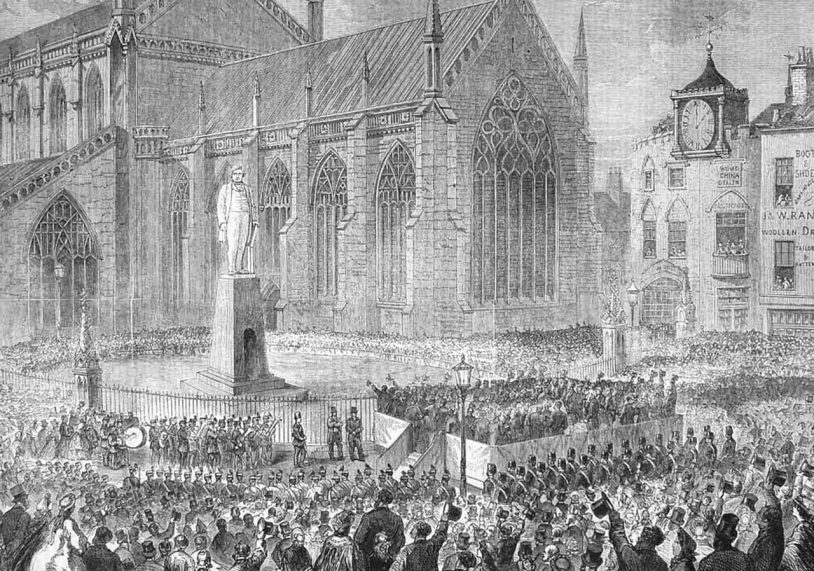

Ingram’s funeral finally took place on Thursday 11th October and processed through the town from the house of Nathanial Webb to Liquorpond Street, West Street, Bridge Street and into the Market Place.

10,000 people lined the streets to pay their respects and a procession of 2,000 people included the 1st Lincolnshire Artillery Volunteers, 4th Lincolnshire Rifle Volunteers, the town’s Mayor, magistrates, corporation, plus its freemasons, odd fellows and foresters, artisans, clergy, and ministers. On that day, too, all of the businesses and shops in Boston’s town centre were closed, and 50 members of staff from the ILN were present.

Herbert Ingram is buried in the cemetery with a memorial to mark his resting place. Ingram is also remembered by the 1862 Grade II listed statue adjacent to St Botolph’s Church.

The figure was created by Alexander Munro and cast by Elkington on a pink granite plinth, with a figure pouring water to symbolise the businessman bringing water to the town.

In the depiction, Boston’s most famous son still clutches a copy of the ILN he founded and looks over the town’s Market Place satisfied with the legacy that he has left the town, its people and the media more broadly, over 160 years after his death.