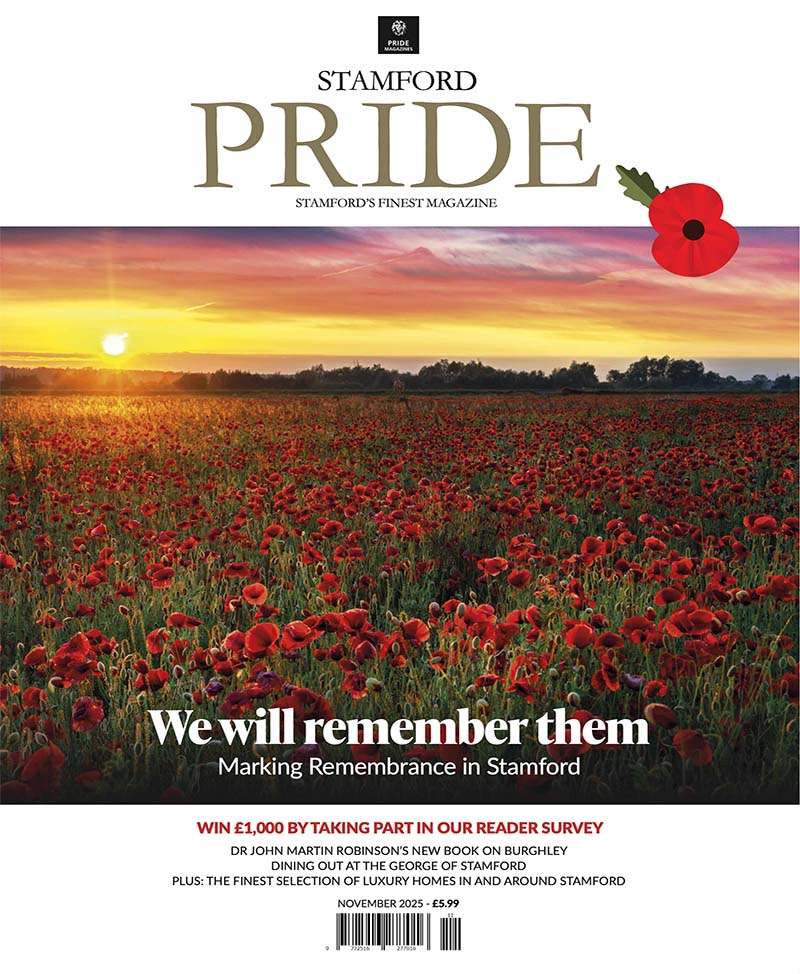

Olympic Lord Burghley

It’s the Olympic performance which inspired a nation and the film Chariots of Fire, released 40 years ago, too. This month we find out more about the 6th Marquess of Exeter and how he competed in the Olympics then sought to unite Europe by bringing the first post-war games to Britain…

Should you let the truth get in the way of a good story? I must confess there have been moments when I’ve embellished in print for the purpose of spinning a good yarn, and the film director David, Lord Puttnam, appeared similarly minded when he directed the film Chariots of Fire, which was released 40 years ago.

The film ostensibly featured the 6th Marquess of Exeter David George Brownlow Cecil, portrayed on screen as Lord Andrew Lindsay, played by Nigel Havers. In fact, there was more than a few liberties taken with the actual events. The lack of accuracy led the Marquess to politely decline involvement in the film’s production and he expressed a preference for his character’s name to be changed because of the lack of accuracy.

David was styled Lord Burghley prior to 1956 and the 6th Marquess of Exeter thereafter, preferring to be known as David Burghley. He was born in 1905 as heir to William Thomas Brownlow Cecil the 5th Marquess of Exeter and Myra Orde-Powlet.

He had two sisters – one older, one younger – plus a younger brother. David was schooled at Institut le Rosey in Switzerland, colloquially known as ‘Rosey’ and then a school renowned for developing ‘multiple intelligences,’ what we’d perhaps know today as simply a rounded education. The school was also renowned for its provision of sports, not least among which was its winter sports, perhaps in part because of its second campus in Gstaad, Bern, where it owned a ski resort about an hour and a half from its main campus.

David completed his education at Eton College and Magdalene College in Cambridge where, already showing athletic promise, he became president of the Cambridge University Athletic Club before graduating in 1927. Three years prior to his graduation, David had competed in the 110-metre hurdles in the 1924 Paris Olympics, among 31 other competitors from 17 nations.

He was aged just 19 and was eliminated in the first round of the event. David, however, was as mentally determined as he was physically fit. In the 1928 Olympics, held in the Netherlands, he competed again and reached the semi-finals of the 110-metre hurdles. He subsequently took part in the 400-metre event and won the race, beating second and third placed Americans Frank Cuhel and Morgan Taylor.

The Commonwealth Games was subsequently devised with the first event held in 1930 in Ontario, Canada. David won both of the hurdling events and was also a member of the team which took gold in the 4 x 400 yards relay event.

At the height of his Olympic career, David was the British record holder in all three hurdle events and the 4 x 400 metre relay. In the high hurdles he was the first Britain to break the 15-second barrier, and won three Amateur Athletic Association of England titles, competing in no fewer than three Olympic Games, setting one world and seven British records in total, as well as winning five AAA titles.

His finest performance in the 4 x 400 relay event came in the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles when he contributed a 46.7 second stage on the British team, helping them to take silver with a new European record of 3:11 seconds. Earlier in the LA games, Burghley had also finished fifth in the 110 metre hurdles and fourth in the 400 metre hurdles with his fastest ever time of 52.2 seconds.

David’s ‘day job’ in politics saw him serving as a member of the Conservative & Unionist Party (the latter part of the name was adopted in 1909, and subsequently dropped, although David Cameron attempted to resurrect its full name). Elected as MP for Peterborough in 1931, he remained in post until 1943 whereupon he resigned his Commons seat to serve as Governor of Bermuda until 1945 whereupon he handed the title to Admiral Sir Ralph Leatham.

At that point, David took up the post of Chairman of the Organising and Executive Committees for the 1948 Olympics, due to take place in London and originally scheduled for 1944. It was the first Olympic event to be held since the 1936 games in Berlin… following which most of Europe became embroiled in another particularly fierce competition.

It was to be the second time that London hosted the games, having hosted them only once before in 1908. The city wouldn’t hold them here again until 2012. Naturally it was significant, too, because of a cross-continent desire to heal wounds after the war and to demonstrate a sense of post-war cooperation between nations. It was not only a sensitive time, but one of austerity too, and indeed the games were nicknamed the Austerity Games owing to the fact that building activities, food and petrol were all rationed.

The 1948 games nonetheless saw 136 medal events, covering 23 disciplines in 17 sports and included art (painting, sculpture, literature and architecture). Art competitions had featured since the 1912 games but the London event was the last time that they served as an element of the Olympics.

The games were deemed a success not least because of David’s input and he continued to serve from 1952 and 1966 as VP of the International Olympic Committee, presenting medals at the 1968 games in Mexico, at which Tommie Smith and John Carlos gave the Black Power salute as David handed them their medals.

The Burghley House Collections still include David’s Olympic medals, one of the few remaining torches which carried the Olympic flame into London in 1948 and his now very unfashionable brown leather training shoes.

David was also married twice; firstly to Lady Mary Theresa Montagu Douglas Scott in 1929 and following the couple’s divorce in 1946, he subsequently married Diana Henderson. The couple had a daughter, Lady Victoria Leatham, née Cecil, whose daughter Miranda Rock née Leatham is the current custodian of Burghley House and serves as Director of the Burghley House Preservation Trust, also established in 1969 by David ‘for the advancement of historic and aesthetic education and the preservation of buildings of national importance, and in particular the preservation and showing of Burghley House near Stamford.’

1981 saw David Puttnam create Chariots of Fire based on the story of two 1924 Olympians, Eric Liddell and Harold Abrahams. The latter competes to overcome his experiences of anti-Semitism, taken on by trainer Sam Mussabini, beaten in the 1924 event’s 200-metres but victorious in the 100-metre event. In the film Liddell is a missionary who refuses to run on a Sunday. He is subsequently unable to compete in his favoured 100-metre event held on that day, and instead is given a place in the 400-metre event by Lord Andrew Lindsay – the character based loosely on David. Liddell’s chances of victory are deemed unlikely in the longer event, but defying expectations he wins the race.

The film shows Abrahams running around the Great Court of Trinity College Cambridge, attempting a lap in the time it takes for the clock to strike 12. In fact, it was David who completed the feat, running 367 metres in 43.6 seconds, and The Great Court Run is still a ritual that students attempt to complete today on the evening of the College’s Matriculation Dinner.

Lord Lindsay – the David Cecil character, doesn’t take part in the Court Run in the film, and neither did Abrahams in real life.

Also in the film, the David Cecil character is seen practising hurdling over Champagne bottles. According to Miranda Rock, he actually used empty matchboxes. Miranda says she loves the film and whilst her mother is in general consensus, Lady Victoria

advises that the story is ‘cobblers!’

What’s not cobblers, however, is the achievements of David and his role in bringing Olympic events to fruition, especially remarkable considering the difficulty in organising the post-war event.

In 2012, the Olympic torch for the most recent London games arrived at Burghley House and was celebrated with The Great Olympic Garden Party in the south gardens, where locals gathered to witness the torch’s arrival live and also on a huge projector screen to ensure the gathering crowds could get a good look.

Also worthy of note is Lord David Cecil, the sixth Marquess of Exeter’s other legacy, bringing The Burghley Horse Trials to the estate from Harewood House. The event was first held in 1961 and though this year’s event has been cancelled due to Covid, it will be back next summer for its 60th anniversary event, with organisers promising big celebrations which will undoubtedly also acknowledge David’s role in the founding of the event in Stamford.