Civic Lincoln

You’ve walked under the Stonebow a thousand times, but now it’s time to stop and admire the city’s rich history, courtesy of Lincoln’s award-winning Guildhall, and its fascinating civic insignia

Back in August, the team at Lincoln’s Guildhall was thrilled to learn that they were to be named one of the top attractions, worldwide, in the Tripadvisor Travellers’ Choice Award. The title places it within the top ten percent of attractions worldwide and it also holds the top spot of the website’s ‘Things to Do in Lincoln’ list.

Unsurprisingly the team are proud not just of the experience they offer to visitors, but of the breadth and quality of history they care for within the building, which also still serves a function as the home of the City of Lincoln Council each month.

Lincoln’s Guildhall

The Guildhall is the ‘official home’ of the Mayor of Lincoln and occupies the entire second floor of the Stonebow. The Stonebow stands on the site of the Roman south gate of Lincoln, where a defended gateway was first constructed as part of the Roman city. There has been a stone arch on this site since that time. The name Stonebow is derived from the Scandinavian words stenni boghe, meaning stone arch, reflecting later influences on the city during the Viking period.

The first recorded use of the Stonebow as a Guildhall dates from 1237. By this time, the Franciscans, also known as the Greyfriars, had arrived in Lincoln and were granted a large site to the south of Silver Street for their friary. King Henry III also gave the Greyfriars the existing Guildhall, which stood next to their new site. As a result, the city’s guildsmen and council were required to leave their former premises and moved into the room above the medieval south gate. This space then became known as The Guildhall. Part of the Greyfriars friary still survives near St Swithin’s Church.

In the late fourteenth century, the City Council petitioned King Richard II for funds to repair the south gate, which had fallen into disrepair and was no longer suitable

for accommodating foreign merchants who came to Lincoln to trade. The King granted the Mayor the right to tax the citizens in order to pay for improvements, and evidence shows the building has been in use continually from this time. The last recorded work took place in 1520 when the south face was remodelled.

The east wing now houses the Mayor’s Parlour but the city gaol was also housed in this wing until 1809, with dungeons below ground. Nearby Saltergate was formerly known as Prison Lane. In 1842 the wing was rebuilt in Ancaster freestone and briefly opened as a Freemasons’ Hall before later being converted into shops and offices.

The Clock and Bell

For many years there was a sundial on the exterior of the Stonebow, but during a storm in 1715, it was blown down. It took more than 100 years before the people of Lincoln could tell the time again, but in 1835, MP John Fardell gifted a mechanical clock to the city that would be illuminated by gaslight.

Another MP, Frederick Harold Kerans, presented a new clock to the city in 1888, initially wound by hand, latterly by electric motor. When the clocks go forward and backwards at the beginning or end of British Summer Time, the Stonebow clock is changed manually… although it does necessitate two people communicating via mobile phone, one person outside, confirming that the correct time has been achieved!

The Mote Bell (from the Old English ‘moot,’ meaning meeting) was cast in 1371 during the mayoralty of William Beele and is one of the oldest of its type in England. The bell is still rung to announce the beginning of a council meeting. It was last repaired in 1949 and it bears the inscription which (when translated from Latin) ‘When anyone rings this bell, the good hear the sound and rejoice that the forum will be filled with the citizenry.’

Inside The Guildhall

Inside the East Wing, a broad oak staircase leads to the Council Chamber above the Stonebow, where meetings of the City Council have been held for centuries. The wooden boards along the staircase list the city’s mayors, sheriffs and town clerks. The Council Chamber itself is a long narrow room with a large oak table (2.2 metres wide, which is greater than the length of two short swords which are 71 cm long, in order to prevent any debates turning bloody!) arranged in a horseshoe, a raised chair for the Mayor and seating for councillors.

The Mayor’s Chair

The Mayor’s Chair dates from 1724 and is richly carved, reflecting its ceremonial importance. It is set within a decorative reredos featuring the carved Royal Arms of King George II, whose reign lasted from 1727 to 1760. These arms are placed on a segmental pediment supported by a pair of Corinthian columns. The presence of the Royal Coat of Arms indicates that this room was historically used as a court of law as well as for civic business.

The back of the chair is elaborately decorated and set beneath a shallow baldachin, or canopy of state. At the upper section is the Cap of Maintenance, a traditional symbol of authority. Below this are carvings of the civic mace and the sword associated with King Richard II, who reigned from 1377 to 1399.

These are shown crossed with two shields placed over them. One shield bears the Arms of the City, while the other displays the Mayor’s seal. The entire composition is framed by a carved ribbon design.

On the Mayor’s desk are two purpose made rests, one for the Mayor’s staff and the other for the mace. The mace is carried into the Council Chamber ahead of the Mayor and placed in position to signify that the Council is formally in session and operating under the Mayor’s authority.

It is always laid with the crown to the Mayor’s right, except when he is attending church, in which case it is turned towards the altar. The mace remains in place until the meeting concludes and it is still ceremonially processed from the Chamber.

The Mayor’s Uniform

The Mayor’s red cloth robe, trimmed with sable and black velvet, has formed part of the civic dress for many centuries. The present robe in use is around seventy years old. Elements of the costume reflect fashions from different periods. The white lace cuffs and jabot, or cravat, recall styles of the eighteenth century, while the black bicorne hat with a gold cockade is associated with the late eighteenth century.

When the Mayor is female, the same ceremonial robes are worn, although the hat takes the form of a tricorne with three points. The Mayor’s chain of office is worn over the robe. These robes are reserved for ceremonial duties and for full meetings of the City Council. When dressed in this way, the Mayor also carries the staff of office, which dates from 1581.

The staff is made from Brazil wood, a red dye wood imported from South America, and is fitted with silver caps. One end bears the City Arms, while the other displays the Arms of the Diocese, symbolising the historic connection between the City and the Cathedral.

Members of the Council can be distinguished by the colour of their robes. Councillors who have previously served as Mayor wear maroon robes, while those who have not yet held the office wear robes of royal blue.

VIPs and Royal Visits

Lincoln’s Guildhall has a long association with the monarchy. The 20th century saw King George V and Queen Mary visit in late 1918 to thank the city for its efforts during The Great War, recognising Lincoln’s production of tanks and early aircraft.

Queen Elizabeth II visited in 1996 to open the University of Lincoln’s Brayford campus. The Queen visited again in 2000 to present the Maundy Money at Lincoln Cathedral, and was pictured at The County Assembly Rooms with MP Gillian Merron, Bridget Cracroft-Ely, and Mayor Lorraine Woolley.

In the 1990s, The Guildhall also hosted a festive episode of the BBC’s Songs of Praise. Other celebrities include Omar Sharif who visited in the mid-1980s to see the sword of Richard II, and actor Leslie Nielsen who visited to admire Lincoln’s insignia!

Recognition for Snips

Many monarchs, VIPs and civic dignitaries have played a part in the history of Lincoln’s Guildhall, but few are remembered as fondly as Snips. Back in 1946, Snips, a Sealyham terrier puppy, was offered for sale on Henry Taylor’s market stall on Sincil Street.

The austere post-war years meant that few people would afford to take on a puppy, although passers-by were keen to stroke him. The enterprising market trader was keen to capitalise on this and charged people a penny to stroke Snips, donating the money to charity.

Snips collected over £5,000 for charitable purposes until he died in 1961, not before he was given a silver collar and medals which are now on display as part of Lincoln’s civic insignia.

Lincoln’s Royal Charters

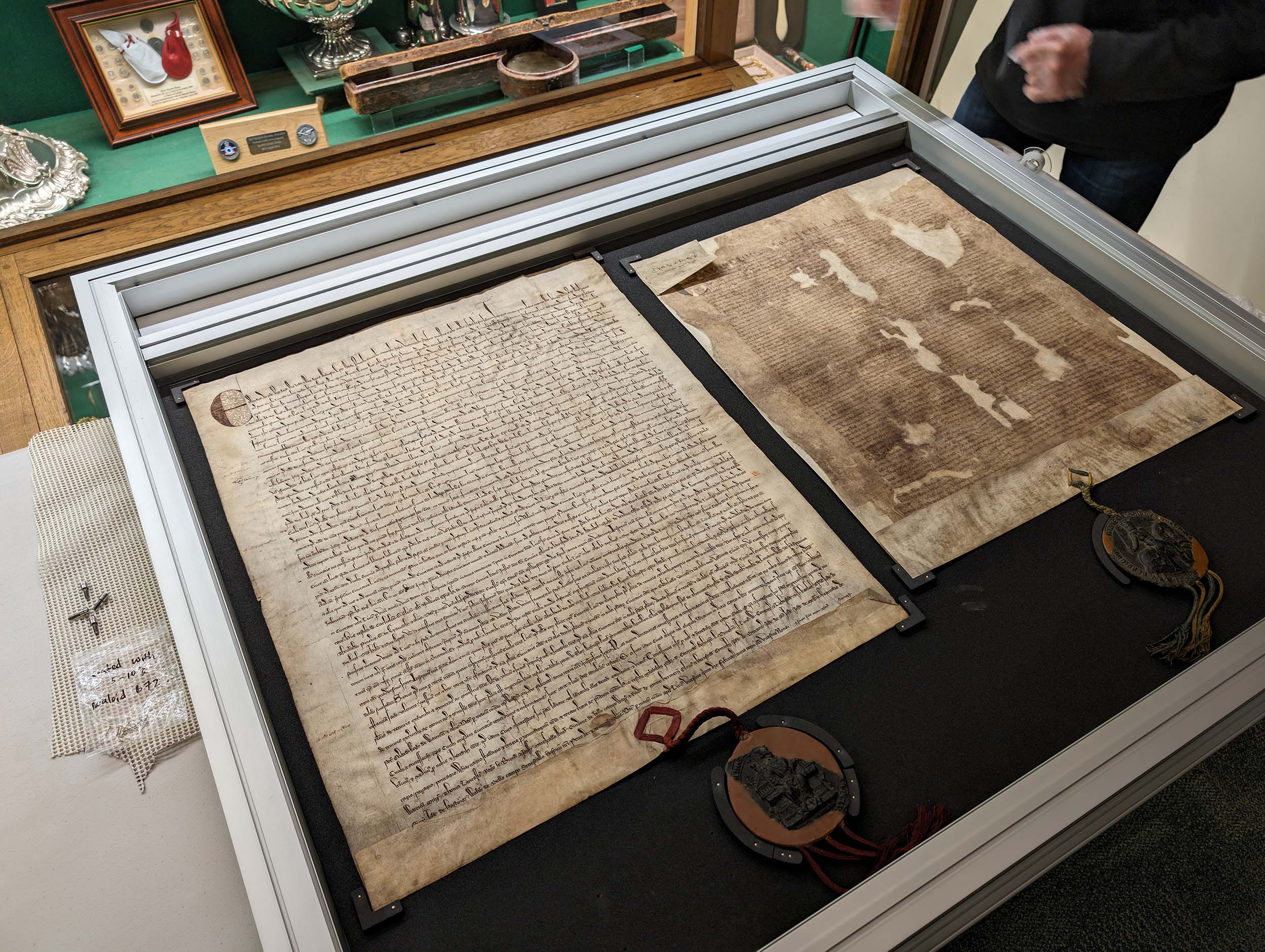

1157 Charter: Henry II

The earliest surviving charter held by the City of Lincoln was granted in 1157 by King Henry II. This foundational document confirmed the liberties, customs and laws from the reigns of Edward the Confessor, William the Conqueror and Henry I. Crucially, it guaranteed that the merchant guild and other traders in the city and county could carry on their business without hindrance. It established the principle that Lincoln’s rights were not simply local custom, but privileges recognised and protected by the Crown.

1200 Charter: King John

Soon after his accession, King John issued a charter in 1200 allowing Lincoln’s citizens to elect two of their own officials to serve as provosts or bailiffs. These officers were responsible for collecting the King’s revenues from the city, a practice known as ‘farming the City’, and the charter enabled civic leaders to raise funds through tolls, fines and rents.

1215: Magna Carta/Charter of the Forest

Magna Carta is not a city charter and isn’t held at the Guildhall. Forming part of the Cathedral collection, it was sealed in 1215 and later reissued. As we’re discussing charters, we still felt it worthy of a mention, given that one of just four copies remain and the document, so closely associated with Lincoln, is on display, albeit at Lincoln Castle. The successive Charter of the Forest (1217), sought to limit royal power over woodland and common land, protecting traditional rights such as grazing and gathering fuel.

1301 Charter: Edward I

In February 1301, King Edward I granted a significant charter to Lincoln while holding Parliament in the city. In practical terms, it confirmed Lincoln’s status as a place of lawful commerce, where civic liberties were recognised by the Crown and recorded in formal terms.

1326 Charter: Edward II

Under King Edward II in 1326, Lincoln was made one of the staple towns for wool, hides and skins. The staple system regulated and taxed trade in key commodities, so designation brought major opportunity. Merchants, financiers and carriers were drawn to staple towns, strengthening Lincoln’s economy. Yet Lincoln later lost this advantage to Boston in 1369, largely due to the silting of the River Witham.

1409 Charter: Henry IV

The 1409 charter of King Henry IV was a landmark for Lincoln’s autonomy. It granted Lincoln the status of a county corporate, making it administratively separate from the wider county, and allowed the city to appoint two sheriffs in place of bailiffs. It also established a yearly fair lasting thirty one days, encouraging trade at a time of decline and helping the city meet its financial obligations to the Crown.

1628 Charter: Charles I

The charter of King Charles I in 1628 became the governing basis of Lincoln’s corporation for centuries. It was a charter of incorporation, establishing a more formal civic structure with a Mayor, Aldermen and Common Council, alongside officers such as coroners and chamberlains.

1685 Charter: Charles II

Issued in 1685, the charter of King Charles II largely confirmed the 1628 arrangements and granted a four day fair and weekly market. It was used only briefly before Lincoln reverted to earlier governance.

1974 Charter: Queen Elizabeth II

The most recent charter was granted by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II in 1974, reaffirming Lincoln’s civic standing.

Lincoln’s Three Ceremonial Swords

Among Lincoln’s civic insignia are four ceremonials swords. The oldest of these is known as the State Sword, which was presented to the city by King Richard II (1377-1399) when he visited the city on his gyration of the Midlands and the North, gathering support for his conflict with the Lords Appellant. The two-handed fighting sword was gifted to John Sutton who was the Mayor of Lincoln at the time, and with it came the formally-granted right to have the sword carried before him on all formal civic occasions.

A double-edged blade around a metre long, the grip is made of wound silver wire and on each side the Royal Arms of King Edward III (1327-1377) is engraved; a shield with the lilies of France and the leopards of England. The Fleur de Lys is engraved on the pommel (the round bit on the handle) along with an inscription added in 1595 which reads Jhesus Est Amor Meus A Deo et Rege (Jesus is my love: from God and the King). The scabbard of the sword dates back to 1902, and was designed by Sir William St John Hope.

Also on display is, The Mourning Sword was presented to the city of Lincoln in 1487 by King Henry VII (1485-1509) when he visited the Cathedral to give thanks for his victory at East Soke near Newark after Royalist forces put down the Earl of Lincoln’s Yorkist rebellion.

The sword belonged to King Henry VII and its original scabbard was decorated with lions, dragons and greyhounds of silver and gold, the heraldic emblems of the King. It is carried in reverse for the funeral of a Mayor who dies in office. The current scabbard dates back to 1685. The Pageant Sword was presented to the city in 1734 by the Mayor John Kent in the hope it would replace the state sword of King Richard II.

The Family Silver

Following the Municipal Corporation Act of 1835, a motion was debated at the new Corporation’s meeting to sell off much of Lincoln’s Insignia for much less than it was worth; just £240. A number of pieces have since been given back to the city including this silver cream jug made by Thomas Wallis and Son (1779) and The Chocolate Pot (1751) presented to the city by Mayor John Wilson in 1751.

Caps of Maintenance

A Cap of Maintenance is a ceremonial hat traditionally gifted to the monarch by the Pope, typically to European sovereigns… although the last English king to be gifted one by the pope was presented to Henry VIII. Lincoln received its first Cap of Maintenance in 1534, with a replacement in 1814. A third Cap was commissioned in 1937 for the Coronation of King George VI, and more recently, in 2006, the 800th anniversary of the office of the Mayor of Lincoln was marked with a new Cap, formally presented to the city and dedicated to HM Queen Elizabeth II. The Cap of Maintenance remains part of the regalia for ceremonial occasions, worn by the sword bearer. All four of Lincoln’s caps remain in the Insignia room of the Guildhall.

Horse Racing

From 1771 to 1964, horse racing was held on Lincoln’s Carholme and the most prestigious race was the Lincoln Handicap. The city possesses five racing cups, including the Lincoln Races Silver Cup and Cover pictured in our feature, dating back to 1836. The cup is still presented to the winner of the show jumping event at the Lincolnshire Show.

Ceremonial Maces

The Mayor’s Mace was presented to the May or of Lincoln by King Charles I in 1640 and was probably made by London silversmith William Mainwaring. Made of silver gilt, it comprises a bowl and open arched crown surmounted by an orb and a cross. The large foot knop ensures it’s (slightly) easier to balance the heavy mace when walking. Also featured in our feature is the Sheriff’s Mace, probably from the Commonwealth period with the arms of Charles II. The timber Sheriff’s mace pictured here is a more modern iteration, rather easier to carry!

Read our full feature in the March edition of Lincolnshire Pride, available at https://www.pridemagazines.co.uk/lincolnshire/view-magazines?magazine=March-2026